Working with View Models in RavenDB

Modern app developers often work with conglomerations of data cobbled together to display a UI page. For example, you’ve got a web app that displays tasty recipes, and on that page you also want to display the author of the recipe, a list of ingredients and how much of each ingredient. Maybe comments from users on that recipe, and more. We want pieces of data from different objects, and all that on a single UI page.

For tasks like this, we turn to view models. A view model is a single object that contains pieces of data from other objects. It contains just enough information to display a particular UI page.

In relational databases, the common way to create view models is to utilize multiple JOIN statements to piece together disparate data to compose a view model.

But with RavenDB, we’re given new tools which enable us to work with view models more efficiently. For example, since we’re able to store complex objects, even full object graphs, there’s less need to piece together data from different objects. This opens up some options for efficiently creating and even storing view models. Raven also gives us some new tools like Transformers that make working with view models a joy.

In this article, we’ll look at a different ways to work with view models in RavenDB. I’ll also give some practical advice on when to use each approach.

Table of contents

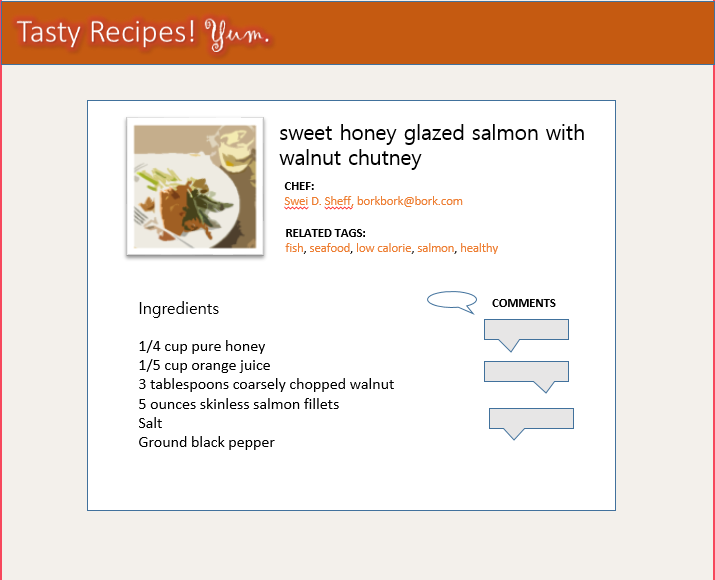

The UI

We’re building a web app that displays tasty recipes to hungry end users. In this article, we’ll be building a view model for a UI page that looks like this:

At first glance, we see several pieces of data from different objects making up this UI.

- Name and image from a Recipe object

- List of Ingredient objects

- Name and email of a Chef object, the author of the recipe

- List of Comment objects

- List of categories (plain strings) to help users find the recipe

A naive implementation might query for each piece of data independently: a query for the Recipe object, a query for the Ingredients, and so on.

This has the downside of multiple trips to the database and implies performance overhead. If done from the browser, we’re looking at multiple trips to the web server, and multiple trips from the web server to the database.

A better implementation makes a single call to the database to load all the data needed to display the page. The view model is the container object for all these pieces of data. It might look something like this:

/// <summary>

/// View model for a Recipe. Contains everything we want to display on the Recipe details UI page.

/// </summary>

public class RecipeViewModel

{

public string RecipeId { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public string PictureUrl { get; set; }

public List<Ingredient> Ingredients { get; set; }

public List<string> Categories { get; set; }

public string ChefName { get; set; }

public string ChefEmail { get; set; }

public IList<Comment> Comments { get; set; }

}How do we populate such a view model from pieces of data from other objects?

How we’ve done it in the past

In relational databases, we tackle this problem using JOINs to piece together a view model on the fly:

// Theoretical LINQ code to perform a JOIN against a relational database.

public RecipeViewModel GetRecipeDetails(string recipeId)

{

var recipeViewModel = from recipe in dbContext.Recipes

where recipe.Id == 42

join chef in dbContext.Chefs on chef.Id equals recipe.ChefId

let ingredients = dbContext.Ingredients.Where(i => i.RecipeId == recipe.Id)

let comments = dbContext.Comments.Where(c => c.RecipeId == recipe.Id)

let categories = dbContext.Categories.Where(c => c.RecipeId == recipeId)

select new RecipeViewModel

{

RecipeId = recipe.Id

Name = recipe.Name,

PictureUrl = recipe.PictureUrl,

Categories = categories.Select(c => c.Name).ToList(),

ChefEmail = chef.Email,

ChefName = chef.Name,

Ingredients = ingredients.ToList(),

Comments = comments.ToList()

};

return recipeViewModel;

}It’s not particularly beautiful, but it works. This pseudo code could run against some object-relational mapper, such as Entity Framework, and gives us our results back.

However, there are some downsides to this approach.

- Performance: JOINs and subqueries often have a non-trivial impact on query times. While JOIN performance varies per database vendor, per the type of column being joined on, and whether there are indexes on the appropriate columns, there is nonetheless a cost associated with JOINs and subqueries. Queries with multiple JOINs and subqueries only add to the cost. So when your user wants the data, we’re making him wait while we perform the join.

- DRY modeling: JOINs often require us to violate the DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) principle. For example, if we want to display Recipe details in a different context, such as a list of recipe details, we’d likely need to repeat our piece-together-the-view-model JOIN code for each UI page that needs our view model.

Can we do better with RavenDB?

Using .Include

Perhaps the easiest and most familiar way to piece together a view model is to use RavenDB’s .Include.

// Query for the honey glazed salmon recipe

// and .Include the related Chef and Comment objects.

var recipe = ravenSession.Query<Recipe>()

.Include(r => r.ChefId)

.Include(r => r.CommentIds)

.Where(r => r.Name == "Sweet honey glazed salmon")

.First();

// No extra DB call here; it's already loaded into memory via the .Include calls.

var chef = ravenSession.Load<Chef>(recipe.ChefId);

// Ditto.

var comments = ravenSession.Load<Comment>(recipe.CommentIds);

var recipeViewModel = new RecipeViewModel

{

RecipeId = recipe.Id,

Name = recipe.Name,

PictureUrl = recipe.PictureUrl,

ChefEmail = chef.Email,

ChefName = chef.Name,

Comments = comments.ToList(),

Ingredients = recipe.Ingredients,

Categories = recipe.Categories

};In the above code, we make a single remote call to the database and load the Recipe and its related objects.

Then, after the Recipe returns, we can call session.Load to fetch the already-loaded related objects from memory.

This is conceptually similar to a JOIN in relational databases. Many devs new to RavenDB default to this pattern out of familiarity.

Better modeling options, fewer things to .Include

One beneficial difference between relational JOINs and Raven’s .Include is that we can reduce the number of .Include calls due to better modeling capabilities. RavenDB stores our objects as JSON, rather than as table rows, and this enables us to store complex objects beyond what is possible in relational table rows. Objects can contain encapsulated objects, lists, and other complex data, eliminating the need to .Include related objects.

For example, logically speaking, .Ingredients should be encapsulated in a Recipe, but relational databases don’t support encapsulation. That is to say, we can’t easily store a list of ingredients per recipe inside a Recipe table. Relational databases would require us to split a Recipe’s .Ingredients into an Ingredient table, with a foreign key back to the Recipe it belongs to. Then, when we query for a recipe details, we need to JOIN them together.

But with Raven, we can skip this step and gain performance. Since .Ingredients should logically be encapsulated inside a Recipe, we can store them as part of the Recipe object itself, and thus we don’t have to .Include them. Raven allows us to store and load Recipe that encapsulate an .Ingredients list. We gain a more logical model, we gain performance since we can skip the .Include (JOIN in the relational world) step, and our app benefits.

Likewise with the Recipe’s .Categories. In our Tasty Recipes app, we want each Recipe to contain a list of categories. A recipe might contain categories like [“italian”, “cheesy”, “pasta”]. Relational databases struggle with such a model: we’d have to store the strings as a single delimited string, or as an XML data type or some other non-ideal solution. Each has their downsides. Or, we might even create a new Categories table to hold the string categories, along with a foreign key back to their recipe. That solution requires an additional JOIN at query time when querying for our RecipeViewModel.

Raven has no such constraints. JSON documents tend to be a better storage format than rows in a relational table, and our .Categories list is an example. In Raven, we can store a list of strings as part of our Recipe object; there’s no need to resort to hacks involving delimited fields, XML, or additional tables.

RavenDB’s .Include is an improvement over relational JOINs. Combined with improved modeling, we’re off to a good start.

So far, we’ve looked at Raven’s .Include pattern, which is conceptually similiar to relational JOINs. But Raven gives us additional tools that go above and beyond JOINs. We discuss these below.

Transformers

RavenDB provides a means to build reusable server-side projections. In RavenDB we call these Transformers. We can think of transformers as a C# function that converts an object into some other object. In our case, we want to take a Recipe and project it into a RecipeViewModel.

Let’s write a transformer that does just that:

/// <summary>

/// RavenDB Transformer that turns a Recipe into a RecipeViewModel.

/// </summary>

public class RecipeViewModelTransformer : AbstractTransformerCreationTask<Recipe>

{

public RecipeViewModelTransformer()

{

TransformResults = allRecipes => from recipe in allRecipes

let chef = LoadDocument<Chef>(recipe.ChefId)

let comments = LoadDocument<Comment>(recipe.CommentIds)

select new RecipeViewModel

{

RecipeId = recipe.Id,

Name = recipe.Name,

PictureUrl = recipe.PictureUrl,

Ingredients = recipe.Ingredients,

Categories = recipe.Categories,

ChefEmail = chef.Email,

ChefName = chef.Name,

Comments = comments

};

}

}In the above code, we’re accepting a Recipe and spitting out a RecipeViewModel. Inside our Transformer code, we can call .LoadDocument to load related objects, like our .Comments and .Chef. And since Transformers are server-side, we’re not making extra trips to the database.

Once we’ve defined our Transformer, we can easily query any Recipe and turn it into a RecipeViewModel.

// Query for the honey glazed salmon recipe

// and transform it into a RecipeViewModel.

var recipeViewModel = ravenSession.Query<Recipe>()

.TransformWith<RecipeViewModelTransformer, RecipeViewModel>()

.Where(r => r.Name == "Sweet honey glazed salmon")

.First();This code is a bit cleaner than calling .Include as in the previous section; there are no more .Load calls to fetch the related objects.

Additionally, using Transformers enables us to keep DRY. If we need to query a list of RecipeViewModels, there’s no repeated piece-together-the-view-model code:

// Query for all recipes and transform them into RecipeViewModels.

var allRecipeViewModels = ravenSession.Query<Recipe>()

.TransformWith<RecipeViewModelTransformer, RecipeViewModel>()

.ToList();Storing view models

Developers accustomed to relational databases may be slow to consider this possibility, but with RavenDB we can actually store view models as-is.

It’s certainly a different way of thinking. Rather than storing only our domain roots (Recipes, Comments, Chefs, etc.), we can also store objects that contain pieces of them. Instead of only storing models, we can also store view models.

var recipeViewModel = new RecipeViewModel

{

Name = "Sweet honey glazed salmon",

RecipeId = "recipes/1",

PictureUrl = "http://tastyrecipesyum.com/recipes/1/profile.jpg",

Categories = new List<string> { "salmon", "fish", "seafood", "healthy" },

ChefName = "Swei D. Sheff",

ChefEmail = "borkbork@bork.com",

Comments = new List<Comment> { new Comment { Name = "Dee Liteful", Content = "I really enjoyed this dish!" } },

Ingredients = new List<Ingredient> { new Ingredient { Name = "salmon fillet", Amount = "5 ounce" } }

};

// Raven allows us to store complex objects, even whole view models.

ravenSession.Store(recipeViewModel);This technique has benefits, but also trade-offs:

- Query times are faster. We don’t need to load other documents to display our Recipe details UI page. A single call to the database with zero joins – it’s a beautiful thing!

- Data duplication. We’re now storing Recipes and RecipeViewModels. If an author changes his recipe, we may need to also update the RecipeViewModel. This shifts the cost from query times to write times, which may be preferrable in a read-heavy system.

The data duplication is the biggest downside. We’ve effectively denormalized our data at the expense of adding redundant data. Can we fix this?

Storing view models + syncing via RavenDB’s Changes API

Having to remember to update RecipeViewModels whenever a Recipe changes is error prone. Responsibility for syncing the data is now in the hands of you and the other developers on your team. Human error is almost certain to creep in — someone will write new code to update Recipes and forget to also update the RecipeViewModels — we’ve created a pit of failure that your team will eventually fall into.

We can improve on this situation by using RavenDB’s Changes API. With Raven’s Changes API, we can subscribe to changes to documents in the database. In our app, we’ll listen for changes to Recipes and update RecipeViewModels accordingly. We write this code once, and future self and other developers won’t need to update the RecipeViewModels; it’s already happening ambiently through the Changes API subscription.

The Changes API utilizes Reactive Extensions for a beautiful, fluent and easy-to-understand way to listen for changes to documents in Raven. Our Changes subscription ends up looking like this:

// Listen for changes to Recipes.

// When that happens, update the corresponding RecipeViewModel.

ravenStore

.Changes()

.ForDocumentsOfType<Recipe>()

.Subscribe(docChange => this.UpdateViewModelFromRecipe(docChange.Id));Easy enough. Now whenever a Recipe is added, updated, or deleted, we’ll get notified and can update the stored view model accordingly.

Indexes for view models: let Raven do the hard work

One final, more advanced technique is to let Raven do the heavy lifting in mapping Recipes to RecipeViewModels.

A quick refresher on RavenDB indexes: in RavenDB, all queries are satisfied by an index. For example, if we query for Recipes by .Name, Raven will automatically cretate an index for Recipes-by-name, so that all future queries will return results near instantly. Raven then intelligently manages the indexes it’s created, throwing server resources behind the most-used indexes. This is one of the secrets to RavenDB’s blazing fast query response times.

RavenDB indexes are powerful and customizable. We can piggy-back on RavenDB’s indexing capabilities to generate RecipeViewModels for us, essentially making Raven do the work for us behind the scenes.

First, let’s create a custom RavenDB index:

/// <summary>

/// RavenDB index that is run automatically whenever a Recipe changes. For every recipe, the index outputs a RecipeViewModel.

/// </summary>

public class RecipeViewModelIndex : AbstractIndexCreationTask<Recipe>

{

public RecipeViewModelIndex()

{

Map = allRecipes => from recipe in allRecipes

let chef = LoadDocument<Chef>(recipe.ChefId)

let comments = LoadDocument<Comment>(recipe.CommentIds)

select new RecipeViewModel

{

RecipeId = recipe.Id,

Name = recipe.Name,

PictureUrl = recipe.PictureUrl,

Ingredients = recipe.Ingredients,

Categories = recipe.Categories,

ChefEmail = chef.Email,

ChefName = chef.Name,

Comments = comments

};

StoreAllFields(Raven.Abstractions.Indexing.FieldStorage.Yes);

}

}In RavenDB, we use LINQ to create indexes. The above index tells RavenDB that for every Recipe, we want to spit out a RecipeViewModel.

This index definition is similiar to our transformer definition. A key difference, however, is that the transformer is applied at query time, whereas the index is applied asynchronously in the background as soon as a change is made to a Recipe. Queries run against the index will be faster than queries run against the transformer: the index is giving us pre-computed RecipeViewModels, whereas our transformer would create the RecipeViewModels on demand.

Once the index is deployed to our Raven server, Raven will store a RecipeViewModel for each Recipe.

Querying for our view models is quite simple and we’ll get results back almost instantaneously, as the heavy lifting of piecing together the view model has already been done.

// Load up the RecipeViewModels stored in our index.

var recipeViewModel = ravenSession.Query<RecipeViewModel, RecipeViewModelIndex>()

.Where(r => r.Name == "Sweet honey glazed salmon")

.ProjectFromIndexFieldsInto<RecipeViewModel>()

.First();Now whenever a Recipe is created, Raven will asynchronously and intelligently execute our index and spit out a new RecipeViewModel. Likewise, if a Recipe, Comment, or Chef is changed or deleted, the corresponding RecipeViewModel will automatically be updated. Nifty!

Storing view models is certainly not appropriate for every situation. But some apps, especially read-heavy apps with a priority on speed, might benefit from this option. I like that Raven gives us the freedom to do this when it makes sense for our apps.

Conclusion

In this article, we looked at using view models with RavenDB. Several techniques are at our disposal:

- .Include: loads multiple related objects in a single query.

- Transformers: reusable server-side projections which transform Recipes to RecipeViewModels.

- Storing view models: Essentially denormalization. We store both Recipes and RecipeViewModels. Allows faster read times at the expense of duplicated data.

- Storing view models + .Changes API: The benefits of denormalization, but with code to automatically sync the duplicated data.

- Indexes: utilize RavenDB’s powerful indexing to let Raven denormalize data for us automatically, and automatically keeping the duplicated data in sync. The duplicated data is stashed away as fields in an index, rather than as distinct documents.

For quick and dirty scenarios and one-offs, using .Include is fine. It’s the most common way of piecing together view models in my experience, and it’s also familiar to devs with relational database experience. And since Raven allows us to store things like nested objects and lists, there is less need for joining data; we can instead store lists and encapsulated objects right inside our parent objects where it makes sense to do so.

Transformers are the next widely used. If you find yourself converting Recipe to RecipeViewModel multiple times in your code, use a Transformer. They’re easy to write, typically small, and familiar to anyone with LINQ experience. Using them in your queries is a simple one-liner that keeps your query code clean and focused.

Storing view models is rarely used, in my experience, but it can come in handy for read-heavy apps or for UI pages that need to be blazing fast. Pairing this with the .Changes API is an appealing way to automatically keep Recipes and RecipeViewModels in sync.

Finally, we can piggy-back off Raven’s powerful indexing feature to have Raven automatically create, store, and synchronize both RecipeViewModels for us. This has a touch of magical feel to it, and is an attractive way to get great performance without having to worry about keeping denormalized data in sync.

Using these techniques, RavenDB opens up some powerful capabilities for the simple view model. App performance and code clarity benefit as a result.

Woah, already finished? 🤯

If you found the article interesting, don’t miss a chance to try our database solution – totally for free!