Best Database for High Availability

Inevitable failure and seamless recovery – a response to the Cloudflare postmortem post discussing a recent outage lasting for several hours.

I found it fascinating to look at what happened and compare it to how RavenDB would behave in such a situation. I have been working non-stop on RavenDB for the better part of a decade in no small part to reduce the amount of complexity that the user must deal with. A database should be felt, not sweated over.

In the case of Cloudflare, the trigger for was a failure in a router. It wasn’t a simple failure. Surprisingly enough, when talking about failures, it is so much better if systems that fail would just die. That is a very well understood scenario, after all.

Things gets a lot more complicated when the failure mode isn’t a binary property of the system being up or down. In this case, the failed router was still up, able to route some packets, but not all of them. That meant, that some of the network paths with the Cloudflare datacenter just experienced a greatly reduced network availability.

Busy running non-stop election campaigns

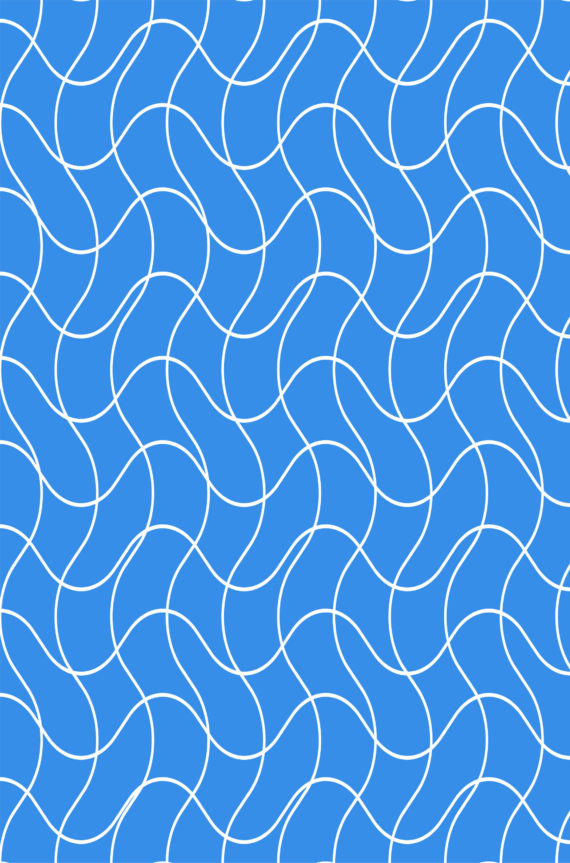

You can see how this looks like on the diagram below. Cloudflare is using ETCD for its control plane, and that uses a consensus protocol named Raft. Skipping a lot of details, that means that in a cluster of three nodes, at least two nodes need to be continuously available for the cluster to continue forward progress.

In this case, however, Node 3 observed that Node 1 was flakey, since it couldn’t get a stable network connection to it. That led it to try to get itself elected as the new leader for the cluster. But when Node 3 won the election, Node 1 would perceive it as unstable and call for another election, and so on and so forth.

The end result was that all the members on the cluster were up, running and busy running non-stop election campaigns. What they weren’t doing is their actual job, which started a cascade of events in the system.

The scenario that triggers the fault

One of the common usages of ETCD is as a reliable coordination mechanism between distributed portions of the environment. In this case, ETCD was used to decide who is the primary database node between two clusters on separate data centers. With ETCD being down, that broke down and a node promoted itself to be a primary.

You can think about this as a dead man’s trigger. If no one else claimed the primary spot, then this node will take it. However, switching primaries exposed an issue with the underlying database. Before the database’s replica could be used, they had to sync completely from the new primary.

Note that the data in question was the identical, hence the issue. The service using this database has enough load that it requires multiple replicas to manage. Until the replicas were backed up, the load was impacting externally visible systems quite heavily.

When reading the postmortem, I was strongly reminded of the “How Complex System Fail” paper, now available at the appropriately named: https://how.complexsystems.fail URL. This is a short paper, but it had a profound effect on how I think and design my software.

Complex systems fail not because of a single cause. The bad router wasn’t the root cause for the Cloudflare outage. Instead, it was the trigger. You needed multiple, unrelated failures to all happen at the same time for the system to actually exhibit failure. Complex systems are often operating in partial failure mode, but there are compensating features to manage it, to avoid actual failure.

What is truly impressive with the Cloudflare postmortem is what they don’t say. When reading their account of the event, I had to stop and triple check the details that they discussed. The scenario that, in the diagram, triggers the fault, is one that has been routinely discussed in the context of Raft implementation.

There are mitigating measures to avoid it, usually called the Pre-Vote feature. I had the pleasure of writing multiple Raft implementations, and handling rouge nodes was something that we took care of each time as a routine part of implementing the protocol. Looking at ETCD, it implements a Pre-Vote feature.

It appears that this is enabled using a flag, and I assume that Cloudflare didn’t turn this on for some reason. I’m guessing, but I assume that this is off by default, or that they first deployed a version that didn’t have it and didn’t modify the configuration on update.

Map the concurrent events

I mentioned that I didn’t believe my eyes at first when reading the postmortem. That was because I didn’t believe that Cloudflare could run their system for as long as they have without running into this exact behavior. I think that this is an example of being hoisted by your own excellence. They run their network well enough that partial failure modes simply never happened to them.

For people who don’t have the expertise of Cloudflare in running networks, this isn’t Byzantine failure. This isn’t something that is out of the ordinary. This is a regular Wednesday.

Using the How Complex System Fail model, we can map the concurrent events that had to happen for the failure to happen:

- The ETCD cluster setup without the Pre-Vote config

- The faulty router

- Automatic promotion of a database to primary

- The bug in switching primaries requiring re-sync of replicas

- The load on the service being too high for a single node to carry even for a short while

They needed each of those events to happen in order for the failure to happen. For example, the router automatically fixed itself after 6 minutes. If Cloudflare didn’t have automatic promotion to primary on a short interval, the issue would have been very minor, a few minutes of potentially degraded service, not the multi hour effect that actually took place.

RavenDB Maximum Survivability

When designing RavenDB, I took to heart the guidance from How Complex Systems Fail and the Release It! book, among other hard won lessons. Looking at the Cloudflare outage, I can project how RavenDB would behave in similar circumstances.

RavenDB also uses the Raft consensus protocol for its cluster management, but unlike the Cloudflare version, Pre-Vote is part and parcel of how the RavenDB’s implementation operates. RavenDB is frequently deployed on the field, which means bad networks, running over partially connected mode, etc. You could say that we have been immunized for such environment because of long exposure.

RavenDB also uses a zero-cost failover mode. A switch in the active node is not a major event for us and will routinely happen during normal operations. Both clients and servers in RavenDB has their own well-defined role in handling and recovering from failures. The clients will receive the failover behavior from the cluster on first connection and the servers will ensure that it is kept up to date as things change.

A node failure will be managed by the cluster, while the clients will simply switch to the next node in the queue. It isn’t uncommon to see different clients who has different network behaviors select different nodes in the same cluster at the same time to operate with.

Multi-Master Topology

Unlike most databases, RavenDB is capable to work in a multi-master topology. Any node in the cluster is able to accept reads and writes. This ensures maximum survivability for the system in the presence of failures, be their full or partial.

RavenDB also adjust to load on the fly. RavenDB is able to reduce background operations and even halt them completely in order to handle increases in load. The server can prioritize answering queries and processing transactions over other responsibilities. A sudden spike of load on the system will cause RavenDB to automatically shed some of the load that can be delayed for later, in order to ensure liveliness of the entire system.

RavenDB’s frequent use on the edge means that it is often running on older hardware. Be it an old PC in a closet somewhere or a Raspberry Pi that was drafted to be a server. This is a much harsher environment than a professionally run data center.

For one of our customers, the only staff at hand to handle any problems is a teenager earning minimum wage. The most complex IT operation that you can expect is “did you turn it off and on again”? The expectation is that the database will continue to work seamlessly and transparently, under all loads and conditions.

We work hard to ensure that regardless of the failure mode that you run into, RavenDB will automatically adjust and overcome. Sometimes that is done with sophisticated algorithms, situational awareness, and fancy behavior. Sometimes this is the result of the school of hard knocks.

All of this is so when you put RavenDB inside a properly run datacenter… things can really fly. If something bad were to happen, we know how to deal with it.

Woah, already finished? 🤯

If you found the article interesting, don’t miss a chance to try our database solution – totally for free!