NoSQL Document-Oriented Databases: A Detailed Overview

What are document-oriented databases?

The document-oriented databases or NoSQL document store is a modernised way of storing data as JSON rather than basic columns/rows — i.e. storing data in its native form.

This storage system lets you retrieve, store, and manage document-oriented information — it’s a very popular category of modern NoSQL databases, used by the likes of MongoDB, Cosmos DB, DocumentDB, SimpleDB, PostgreSQL, OrientDB, Elasticsearch and RavenDB.

This semistructured data lets you handle challenges that are harder to get a grip on with RDBMSs:

- When a database requires a change in its model. Relational databases require developers to request the database administrator to step in. With more people in the chain, newer companies still in rapid growth can hardly afford these inefficiencies.

- A rigid data structure with columns and rows — where one column insertion affects the whole table — is ill-fitted for agile software development which needs adaptable processes and faster software shipment.

- The relational model (RDBMS) can be oversimplified — a flat data structure: columns and rows is not a natural way to store data. Dividing it into columns is less flexible than more complex data schemas seen in document-oriented databases.

Centred around JSON-like documents, document stores make a natural and flexible solution for developers that can work faster with agile software with superior developer productivity, which is why the document data model in modern NoSQL databases has become a popular alternative to tabular RDBMS.

XML and graph databases

A quick word on these two: XML is a subclass of document-oriented databases, but streamlined for XML documents. Graphs are a similar thing, but with an additional layer (the relationship) which adds a document linkage function for fast traversal. Note that most XML databases are indeed document-orientated.

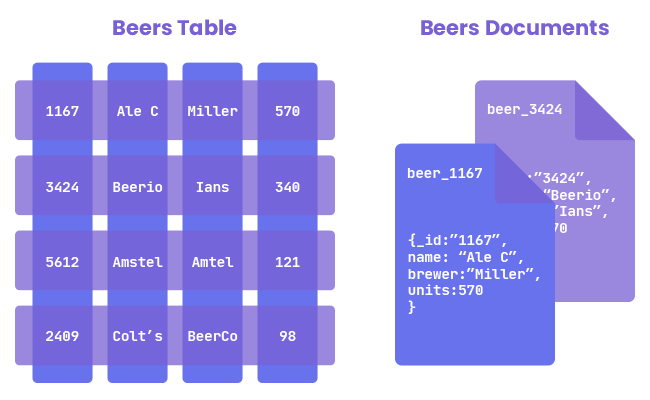

How document databases differ from relational databases

Document databases are significantly different in function to traditional relational databases.

Relational databases typically store data in separate, linked tables (as defined by the programmer), allowing single objects to be spread across several tables. But, in document databases, all information for a given document or object is stored in a single instance — there is no need to do object-relational mapping when loading data into the database, or when retrieving things.

Document databases are typically faster for this reason, although this is incumbent on how you use it: jump to the pros and cons for more on this.

Flexible Schemas

Rather than the tabular model, document stores have a dynamic self-describing schema, adaptable to change. No need to predefine it is the database. Values and fields can alternate through different documents; modify the design at any stage, without fundamentally disrupting its structure — no need for schema migrations. Note: some document stores allow JSON schema, letting you set governing rules for managing document structures.

Better for Agile Developers

Due to the intuitive data model, document-oriented databases are faster and easier for developers. The objects in your code can be mapped to the documents, making them more intuitive to handle. Decomposition of data across tables is eliminated as a necessity, along with the need to integrate a separate ORM layer, or using costly JOINs.

Powerful Querying

Query in a flexible way, with the expressive query language and multifaceted indexing feature. This is an essential difference between relational databases and document stores. The query language has comprehensive abilities, letting you deal with data however you think is best. Full-time aggregations, ad hoc queries, and indexing are deep ways of processing, modifying, and retrieving your data. ACID transactions let you retain guarantees you are accustomed to having in SQL databases, whether this is manipulation of data in single documents or in shard multiples.

Widely Compatible

JSON documents are used in every corner. As a language-independent, human readable, and non data-intensive standard, JSON is widely used for data interchange and storage. Remember that document stores are a subset or superset of other existing data models which means that you can codify data however your application requires — key-value pairs; rich objects; tables; geospatial and time-series data; and graph edges/nodes. Only a single query language is needed to work in documents, adding a consistency to your development workflow whatever data model you have chosen.

Distributed Systems

Distributed systems increase how massively scalable and resilient your data is. While relational databases have a more monolithic framework with incremental scaling-up, document databases are essentially a form of distributed systems. Each document is an independent unit, more easily distributed across servers without destroying data locality. Retain a high level of availability of applications using replication with self-healing recovery. This also allows for isolation of several workloads from one another in a cluster. And native starting allows for application transparent, elastic horizontal scale-out to facilitate workload scaling.

Can’t I just use JSON in a RDBMS?

Relational databases have seen the utility of document stores in granting developers intuitive powers, letting them build faster. So you can now find support for JSON in most relational databases. It’s however not as simple as adding a JSON data option, then receiving the benefits of native document stores. The reason? Relational models break away from developer productivity, rather than adding to it — a few challenges developers have to deal with in relational databases using JSON support:

Unsophisticated Data Schema

RDBMS is restricted to representing the JSON data type as basic numbers and strings rather than rich data types — for the latter, you need a native document database such as RavenDB. Without this, processing, sorting, and comparing your data will be more cumbersome and over-complicated.

Non-native, Finicky Compatibility

For proprietary reasons, features that work naturally with document databases will be troublesome when translating across to your favorite SQL service. All sorts of issues arise here that can affect productivity, including SQL functions specific to each vendor and requiring customizations.

Quality and Rigidity

Expect a lower quality of data, and there is the issue of rigid tables. There is too little that relational databases can do to validate the document schema, restricting the ability to quality-control JSON data. With that, your bog-standard tabular data will still require schema definitions, along with the other costs in table alteration that rises as your application’s abilities develop.

Overall Poor Performance

The bottom line: while you can find JSON support in most relational databases, there is no statistics stored on JSON data — i.e. meaning the query planner cannot optimise queries within documents, and you can’t optimise them. Also note there is no native scaling-out — if you want to partition (shard) your traditional relational database to match workload evolution, you will have to shard for yourself in the application layer, or pay for pricey scale-up systems.

Are documents easier to work with than tables?

Document databases use practical, intuitive modelling that reads faster than relational models. If you add superior indexing, this is boosted further.

Many developers choose Oracle and SQL over NoSQL because they think rows and columns read faster than documents. Document databases have been consuming more of the market share once occupied by relational databases because developers are wizening up to the truth.

Relational databases would be faster if all the info needed per query was contained in a single row. In reality, the query has to search across several locations, retrieving data nested across different tables, then piecing it back together before spitting out the result… Whereas document databases contain all the data you need one location. All you need to do is query it, massively reducing complexity and boosting performance.

Documents: A definition

Documents are at the heart of document-oriented databases. While the definition of a document differs by specific data store implementation, documents are generally assumed to encode encapsulated data (or information) into some standard format/encoding. Encoding types include JSON, XML, YAML, and binary types such as BSON.

You can roughly correlate documents as a concept with that of an object. There’s no need for a rigid or standard design/schema, and you can alternate the slots, parts, keys or sections. Document stores allow for different types of documents in each store, the fields inside each as optional. You can often encode with different coding systems too. For instance, here is a document encoded in JSON:

{

"FirstName": "Tom",

"Address": "6 Harry St.",

"Hobby": "stamps"

}

You might, however, have a second document encoded in XML as:

<contact>

<firstname>Harry</firstname>

<lastname>Potter</lastname>

<phone type="Cell">(123) 555-0888</phone>

<phone type="Work">(230) 555-0123</phone>

<address>

<type>Mobile</type>

<street1>4 Privet Dv.</street1>

<city>Boys</city>

<state>AR</state>

<zip>31115</zip>

<country>US</country>

</address>

</contact>

There is unity in the structural composition of each document, but the fields differ. The information and design of the document is typically referred to as the document’s content that we can refer to through editing or retrieval means.

Relational databases by comparison contain all of the same fields, with some unused if there is no data for them. Whereas documents contain no empty fields. New information can be added to records without needing every other record to be updated to share a similar structure. In terms of scalability, if you need to update your document database, you can restrict this to new entries rather than the whole database.

To let you add, change, delete, and query information, each document is given a unique ID. The identifier is not especially important. You can use the complete pathway or a simple number series to refer to documents. When querying information, documents themselves are searched — data is taken directly from the document rather than from columns inside the database.

More

- Manual document revisions with RavenDB

Pros and cons of document stores

On the pro side of things: the main thing to know is that traditional relational databases require the same fields to exist for each information piece — and each entry. When information is unavailable, the cell is empty. However, it still needs to exist in the database. Document-oriented databases have a much more flexible structure, not requiring consistency. And even large amounts of unstructured data can be handled by the database.

Also, new information can much more easily be integrated. There’s no need to add new information fields to every dataset, only the pertinent ones in the document store. You also have the option to add additional fields to existing documents if you wish. Because the information is distributed over multiple related tables — all of it is instead in one single location, which can be a boon to performance.

However document databases don’t quite have the relational capacity; in fact, document stores aren’t well suited to being referenced that way. This is the main con to document stores. As long as you do not try to use relational aspects, don’t try to interlink documents together by fields, then you won’t need to deal with what will likely become very complex and finicky. A relational database is much more well suited to data volumes with high-level networks.

Well-known and recommended document databases

Document databases are especially important for the development of web apps. With this increased need, there’s been a boom in the popularity of document stores inclusions in database management systems (DBMSs) on the market. Here are some well-known and recommended examples (this is not at all exhaustive list):

- RavenDB: The most popular NoSQL database out there, RavenDB was written with C#, using Node.js, Java, Python, Ruby, and .Net. It uses ACID transaction support, or BASE when indexes are involved.

- Base X: An open sourced document store solution using XML and Java. It also comes with a graphical user interface.

- CouchDB: an open-source solution created by Apache Software Foundation. Written with Erlang, using JavaScript, applications like Ubuntu and Facebook use this.

- Elasticsearch: Has a search engine designed on document-orientated databases with JSON encoding.

- eXist: Another open-source DBMS, this uses a Java virtual machine that works on any operating system. XML documents are mostly used.

- MongoDB: A well-known NoSQL database. The application is written with C++ and has JSON–like documents.

- SimpleDB: Written in Erlang, SimpleDB was developed by Amazon for its native DBMS used in the company’s Cloud service. There is a fee to use this service.

Woah, already finished? 🤯

If you found the article interesting, don’t miss a chance to try our database solution – totally for free!